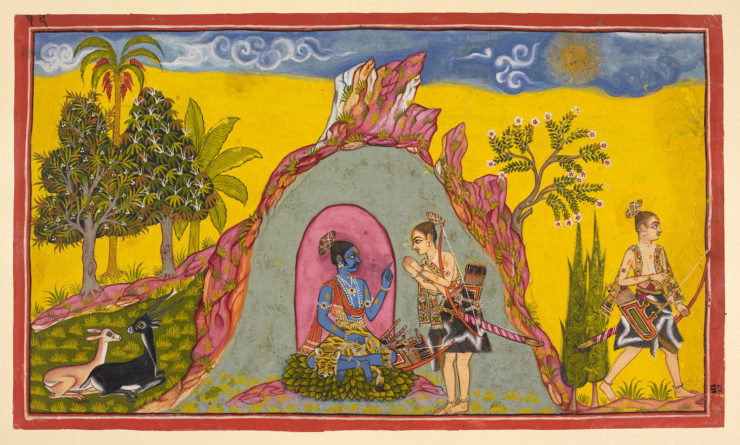

Here’s a version of the Indian epic the Ramayana: Rama is born to King Dasharath of Kosala, who has three wives including Kaikeyi, mother of Bharata. Just as Rama is about to take the throne, Kaikeyi convinces Dasharath to send Rama into exile so that Bharata can be king. Rama’s wife, Sita, and brother accompany him into exile in a faraway forest. Several years into the exile, a demon king, Ravana, who has long coveted Sita, kidnaps Sita and takes her to his kingdom of Lanka. With the help of allies, Rama journeys to Lanka and battles Ravana and his armies. After days of fighting, Rama kills Ravana and reunites with Sita. Rama and Sita return home and become king and queen of Kosala.

I’d like to think that’s one of the least controversial paragraphs on the Ramayana one could write. But this “simple” version, widely accepted by many Hindus, omits beloved characters, overlooks several plot elements, and fails to grapple with the epic’s true complexity. The Ramayana has taken on a life of its own both in Hindu culture and religion, and in Indian political movements. The Ramayana that feeds into these movements is also, in many ways, a fiction, constructed piecemeal out of the original epics to support an uncomplicated narrative where Rama is the hero and Rama’s world is something to aspire to. But there is a long tradition of telling and retelling the Ramayana, one that does not always conform to the mainstream.

The interpretation of living myths has direct implications on people’s daily beliefs and practices, as well as larger social narratives about the groups in these myths. For authors who seek to engage with myths from a living religion, looking beyond the dominant narrative and resisting homogenizing tendencies is imperative. Although I take as my focus the Ramayana, much of this analysis applies to any myth central to still-practiced religion: what is traditionally centered in these myths is not unavoidable but rather chosen. And we can choose differently.

Rama is a beloved Hindu deity. His moving story has inspired deep devotion and even new religious movements . Today’s Hindu nationalism is even based in part around a desire to return to the “Ramarajya”, that is, the rule of Rama, which has developed a connotation of a Hindu country ruled by Hindu ideals . The broader ideology of Hindu nationalism has led to discrimination against religious minorities, caste minorities, and women.

So what does the Ramayana itself have to do with this? The story of Rama has permeated the public conscience, rarely through readings of the original Sanskrit text and more commonly through popular depictions. In the late 1980s, for example, India’s public TV station broadcast a retelling of the Ramayana that reached hundreds of millions of households. Around the same time, Hindu groups began claiming that a mosque in Ayodhya, India had been built on Rama’s original birthplace and advocated for tearing down the mosque to build a temple to Rama. And Rama’s character, in the TV show, referenced the importance of earth from his birthplace, a detail which never appears in the original epic. Just a few years later, riots over Rama’s birthplace ended in the mosque being torn down .

Conflicts over a location in an epic are one thing, but the Ramayana, in its pervasiveness, teaches other lessons by the examples of its characters. In particular, there is the figure of Rama, the prince who always obeys his parents and never backs down from his duty to fight evil, and Rama’s allies, who bravely accompany him into battle. But there are other, less obvious, messages embedded within the story, and as teachings about Rama get taken up, his surroundings are absorbed too. While there are many examples of this phenomenon , the particular group that has inspired my writing is women. Women in the Ramayana often play pivotal roles, despite appearing far less than men, but their critical actions are typically portrayed as occurring through malice or error—they are either virtuous and largely ineffectual or are flawed and central to the plot.

Consider Queen Kaikeyi. In most popular depictions of the Ramayana, Kaikeyi is the catalyst for Rama’s entire journey. But she exiles him out of jealousy and a desire for power, not to help Rama. And the idea of the exile is planted by her maidservant, Manthara, who selfishly does not want Kaikeyi to lose her position as first among queens. Kaikeyi and Manthara stand in contrast to Dasharath’s other wives, Sumitra and Kaushalya. Sumitra is not the mother of Rama but happily supports his ascension, while Kaushalya is Rama’s mother and supports him throughout all his trials although she is unable to alter his exile. Urmila, another prominent wife in the story, is significant because she sleeps through the entire events of the Ramayana, having taken on that burden so her husband, Rama’s brother Lakshmana, never has to sleep.

Once Rama is in exile, it is the female rakshasa Shurpanakha who sets into motion Ravana’s kidnapping of Sita. Shurpanakha is spurned by Rama and when she attacks Sita out of spite, Lakshmana cuts off her nose. Humiliated, Shurpanakha flees to her brother Ravana and complains about Sita, and Ravana, hearing of Sita’s beauty, decides he must possess Sita. It is Shurpanakha’s lust, anger, and spite that leads to Sita’s kidnapping.

Even Sita herself is not immune. On the day she is kidnapped by Ravana, Sita is given protection by Lakshmana so long as she stays inside her cottage. But Ravana convinces her to step outside, and so her kidnapping is in part due to her failure to stay within the boundaries drawn for her. Once Rama wins Sita back, he asks her to undertake the Agni Pariksha, a trial by fire to prove she remained chaste while in captivity. Even after she walks through the flames untouched, Rama later exiles her due to popular belief that Sita cannot be beyond reproach after living in another man’s home.

Where do these messages leave women in Hindu dominated societies today? To be sure, the Indian Supreme Court didn’t cite the Ramayana when it decided it could not declare marital rape a crime. Yet surely the message that a man has the ultimate authority over his wife had something to do with it. Groups of men who try to police women’s “modesty” aren’t referencing Rama or his subjects while they harass and shame women. Yet surely the message that woman is weak and her chastity more important than anything has emboldened this behavior.

But these messages from the Ramayana are not inevitable elements of an ancient epic. They are choices. Authoritative tellings and retellings exist that present different, and often less patriarchal, alternatives. While right wing Hindu groups have complained about the recognition of multiple versions of the Ramayana, going so far as to seek removal of scholarship about this from university syllabuses, these alternatives begin with the “original” source, the Sanskrit Valmiki Ramayana. Most consumption of the Ramayana is through translations, abridgements, and adaptions, which omit material from the Valmiki Ramayana—for example, in Valmiki’s original epic, Kaikeyi’s husband promises that Kaikeyi’s son will be king in exchange for her hand in marriage . This fact rarely, if ever, shows up today, even though it sheds new light on Kaikeyi’s actions: whatever her motivations, she is simply demanding her husband honor his wedding vow!

The Valmiki Ramayana is not the only major version of the Ramayana . Consider one version by the Hindu saint Tulsidas. In the 16th century, he wrote a people’s version of the Ramayana, the Ramacharitmanas, credited as the “most popular version of the story of Rama” —it is written in a Hindi dialect and still widely read. The Ramacharitmanas makes the claim that the goddess of speech, Saraswati, influenced Manthara’s actions . The goddess intervenes because she knows Rama must be exiled to fulfill his divine purpose of slaying Ravana. This interpretation of Manthara’s actions—as sanctioned by the gods so that Rama can succeed in his purpose—fundamentally transforms Manthara’s character. And yet, in popular media today, she remains fully maligned.

Sita, too, comes across differently in these interpretations. The Adbhuta Ramayana, a version of the Ramayana also attributed to Valmiki himself , tells the events of the Ramayana through Sita’s life. In the Adbhuta Ramayana, the ten-headed Ravana is only a minor evil power; the real villain is the thousand-headed Sahastra Ravana. Sahastra Ravana is so powerful that he quickly knocks Rama unconscious. At the sight of her fallen husband, Sita takes on the form of Kali, a powerful goddess associated with death, and destroys Sahastra Ravana. In the Adbhuta Ramayana, Rama awakens to behold this form of Sita and worships her; Sita’s purity is never seriously questioned. Instead, Sita is an equal to her husband, and said to be a representation of the strength within all of humanity.

It is clear, then, that alternative narratives to the mainstream version of the Ramayana can be supported by the canon. A few modern retellings of the Ramayana have pushed on the conventional story by focusing on Sita, rather than Rama, including books like Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni’s Forest of Enchantments and Volga’s The Liberation of Sita. Some of these Sita-centric retellings have even been the subject of criticism for their portrayals of patriarchy. For example, the animated film Sita Sings the Blues (made by a white creator with an Indian cast) in which Sita laments her fate and criticizes her husband’s abandonment was the subject of controversy, with objectors pointing to the portrayal of Sita as “bosomy” and calling it a religious mockery. And the TV show Siya ke Raam aired in India, which sought to portray the events of the Ramayana through the eyes of Sita and other women, was criticized by right wing Hindu groups for denigrating Hinduism by supposedly inventing religious prejudice against women, among other things.

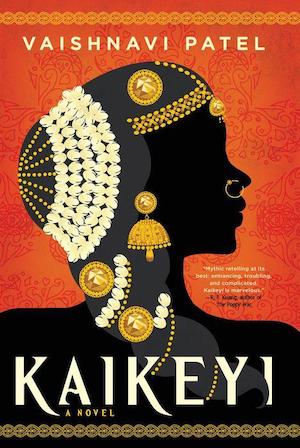

Buy the Book

Kaikeyi

But although these retellings sometimes include maligned women like Shurpanakha or Kaikeyi, they do not linger on these characters. My novel, Kaikeyi, seeks to move beyond the most sympathetic woman of the Ramayana to explore a woman portrayed as wicked and manipulative and instead make her actions reasoned and reasonable. Writing narratives that defy the patriarchy means that we must look at the unpopular women and recognize that perhaps they are unsympathetic because of misogynistic expectations—not as an unshakeable condition of their existence. It is in this space that retellings have the most power to reshape narratives, because they necessarily must challenge tradition.

Of course, the patriarchy, and other social hierarchies, do not exist solely because of myths or stories. It’s impossible to untangle whether the current popular myths of living religions are skewed because they have been chosen by the favored groups or vice versa—it is likely that both are true. But choosing to draw out forgotten elements of a myth can contribute to broadening and complicating mythic stories and the supposed lessons they teach. The Ramayana, and many religious myths, may have been simplified over time, but the roots of these stories are multifaceted, with multiple versions and translations informing the narrative we know today. We are not forced by the source material to turn the Ramayana into a story where women are naïve or malicious or impure. Choosing alternate narratives is not an act of rewriting—it is an act of honoring the foundations of the myth.

Vaishnavi Patel is a law student focusing on constitutional law and civil rights. She likes to write at the intersection of Indian myth, feminism, and anti-colonialism. Her short stories can be found in The Dark and 87 Bedford’s Historical Fantasy Anthology along with a forthcoming story in Helios Quarterly. She was also a Pitch Wars class of 2019 mentee. Vaishnavi grew up in and around Chicago, and in her spare time, enjoys activities that are almost stereotypically Midwestern: knitting, ice skating, drinking hot chocolate, and making hotdish.